Family secrets revealed: DNA analysis identifies the father of chimpanzee Zabari

One father, five candidates

Zabari, the baby chimpanzee born in December 2024, is growing up in a lively group at Antwerp ZOO with no fewer than five adult males. Since virtually every male gets the chance to mate with every female at some point, it is far from easy to pinpoint the father of a newborn. Dominant males may have ‘first pick’, but lower-ranking males also seize opportunities – sometimes on the sly. Females usually go along with this, as winning favour with all the males can increase the safety of their future young. After months of speculation and, above all, painstaking DNA work in Antwerp ZOO’s genetics lab, the pieces of the puzzle finally fell into place: chimpanzee Tambuzi is Zabari’s father.

Parentage research as the key to genetic management

This kind of research goes well beyond simple curiosity. ‘Paternity testing is really just one piece of the puzzle,’ explains Sarah Lafaut, Curator of Mammals at Antwerp ZOO and Planckendael ZOO. ‘What we want to do is map out the animals’ family ties: who is related to whom, and how closely. That may sound obvious, but in a group of chimpanzees – or other social species – it’s often much less clear-cut than it is for humans.’

Genetic management is all about preserving as much variation as possible within a species. And that is precisely why parentage research is so important.

'When animals that are too closely related – essentially close family – have offspring, we call that inbreeding. This can result in hereditary disorders or reduced resistance to disease. By knowing the family lines precisely, we can avoid these risks and keep the species healthy.'

DNA analysis forms the foundation of the European breeding programmes (EEPs), in which zoos work together to ensure that endangered species remain healthy and viable. ‘We record parentage and genetic data in a studbook that is shared across Europe. Based on that, we make breeding recommendations: which animals are a good match, which are not, and in which cases it is better not to breed certain individuals. That may sound strict, but it is vital for the survival of a species,’ adds Lafaut.

Antwerp ZOO and Planckendael ZOO play a coordinating role in this for several species, including the okapi, the bonobo, the Congo peafowl, the golden-headed lion tamarin, the Vietnam pheasant, the cinereous vulture and the Mexican military macaw. Researchers at Antwerp ZOO’s science centre collect and analyse genetic material from all these species and share the results with fellow zoos worldwide.

From a hair sample to a DNA profile

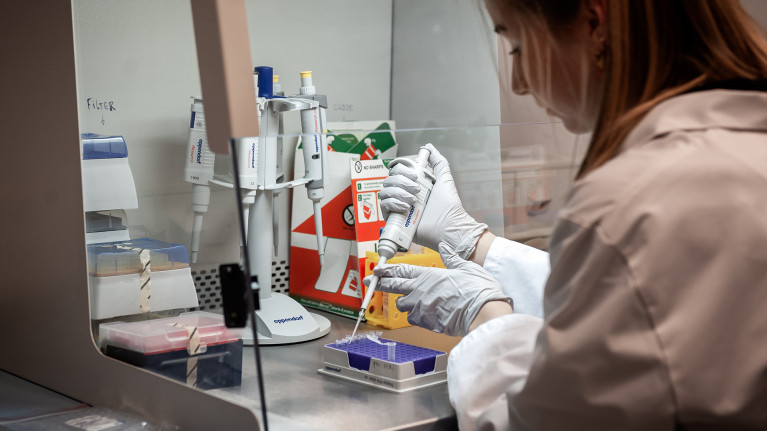

To work out who Zabari’s father is, researchers needed genetic material from the baby chimpanzee, his mother, and all the adult males that were in the group at the time of conception. ‘For Zabari, we opted for a hair sample,’ says Nicky Staes, researcher at Antwerp ZOO and Planckendael ZOO. ‘Just a few hairs with their roots are enough to isolate sufficient DNA. For the mother and the five potential fathers, we were able to use existing blood samples taken earlier during medical procedures. And importantly: we never take blood solely for genetic research. That only happens if an animal is already under anaesthetic for another medical treatment.’

The samples are collected with great care, using gloves to avoid any contamination with human DNA. They are then sealed and taken to the Antwerp ZOO lab. There, researchers break open the cells in the hair roots and blood, and extract the DNA. ‘It’s a bit like following a recipe in the kitchen,’ Staes explains. First, they add a few chemicals. Then the mixture is heated so that the cells burst open and release their DNA. Finally, the tubes go into a centrifuge. As the samples spin at high speed, the heavier cell fragments sink to the bottom, while the DNA remains in the clear liquid at the top.

‘We collected DNA from seven chimpanzees. Every animal – including humans – has DNA that is both inherited and unique. At conception, the mother passes on half of her DNA and the father provides the other half. Together, this makes up a kind of genetic fingerprint that is unique to each individual. To work out who Zabari’s father is, we first looked at which half of his DNA came from his mother. Whatever was left had to come from his father.’

One match, four others ruled out

During the analysis, the pieces of the puzzle quickly fell into place: one of the five adult males was an exact match with the paternal half of Zabari’s DNA. This allowed researchers to confirm the baby chimpanzee’s father beyond any doubt: Tambuzi is the father. With this type of analysis, there is very little room for doubt,’ Staes continues.

The confirmed paternity is recorded in the international studbook, and Zabari’s data will contribute to future breeding recommendations for chimpanzees across Europe.

Diving deeper into DNA

DNA, or deoxyribonucleic acid, is made up of a long sequence of letters (A, T, C and G) that together form a genetic code. Some stretches of DNA naturally contain repeated sequences, such as ‘CTTCTTCTT’. These repeats are called microsatellites, and their length varies from individual to individual.

The pieces of DNA that scientists compare in this way – these microsatellites – are known as genetic markers. By comparing 18 of these markers, we get what can be described as a genetic fingerprint. You can think of it like a barcode: each marker is a stripe, and together they form a unique pattern that can be scanned and compared. Only the chimpanzee that matches every single one of Zabari’s markers can be considered the father.’

Researchers in the lab use a technique called PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction). This is the same technology used in COVID-19 tests and works in a similar way: a sample is taken, chemicals are added, and the lab makes millions of copies of specific stretches of DNA.

DNA as an archive for the future

The research at Antwerp ZOO doesn’t stop here. The samples collected in this study are stored in the zoo’s Biobank, in freezers set at -80°C. Staes concludes: ‘Every sample contains a wealth of information. The wonderful thing about DNA is that it serves as a kind of archive. A single sample can later provide insights for other studies – ranging from hereditary diseases to population structure, or even evolution.’